Going into How to Make a Killing, expectations were admittedly low. The film suffered from minimal promotion and a long-delayed release. This is generally a red flag, echoed by its absence from major festival circuits. And yet, it turns out to be a pleasant surprise. While it doesn’t reinvent the dark comedy wheel, it delivers enough sharp edges and charismatic performances to justify its existence. It works surprisingly well as John Patton Ford’s follow-up to Emily the Criminal, and is another morally murky story about ambition, desperation, and questionable choices.

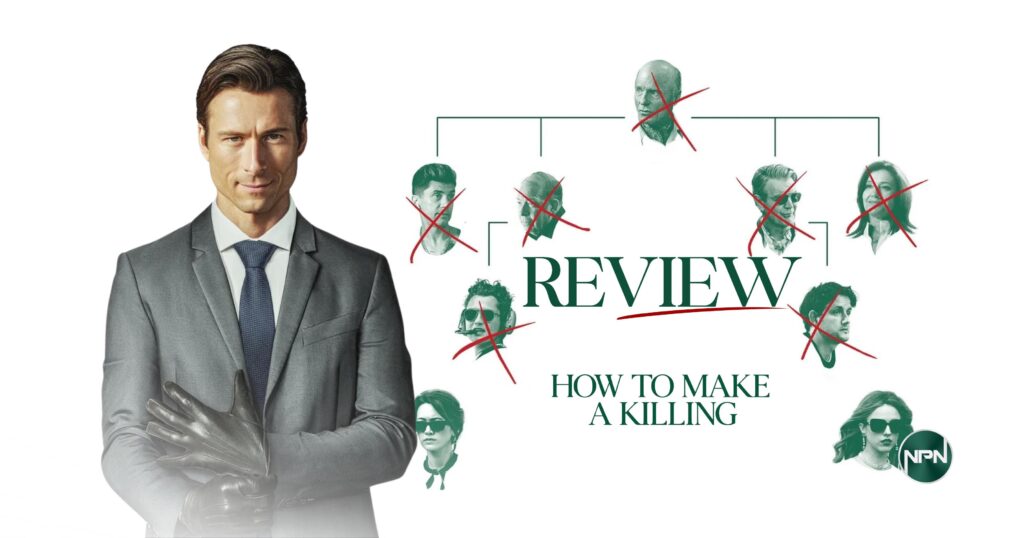

At the center is Glen Powell, who once again proves he can command the screen. There are shades of his effortless charm from HitMan here. His character may be doing objectively bad things, but Powell imbues him with enough wit and self-awareness that you still find yourself rooting for him. Powell’s chemistry with Jessica Henwick is another highlight. Their dynamic gives the story an emotional anchor amidst the chaos. Henwick holds her own with a grounded performance, while Zach Woods steals scenes with his signature awkward unpredictability.

The film’s brisk 100-minute runtime works in its favor, keeping the narrative tight even when the opening act feels rough and overly heavy on exposition. Once the killings begin, however, the momentum noticeably improves. Despite its darkly comic tone, there are plenty of genuinely tense moments that add weight to the escalating chaos. Beneath the surface, the story toys with commentary on aristocracy and privilege, playing with the “eat the rich” concept that questions society. It’s not the sharpest satire in the genre, but it does attempt to play around with morality in interesting ways. It also asks who truly deserves sympathy when greed and entitlement collide.

The kills themselves are inventive and staged with enough personality that almost every character manages to stand out despite limited screen time. That said, the film’s talented ensemble feels underutilized. Ed Harris and Margaret Qualley, in particular, seem underserved by the screenplay. Qualley still manages to be deliciously sinister in a handful of moments, but you can’t shake the feeling that both actors deserved meatier arcs. It’s emblematic of the film’s biggest issue: a lack of narrative substance. The screenplay could have been more fleshed out, giving its strong cast richer material to work with. That thinness perhaps explains why it skipped major film festivals.

Tonally, it’s a decent dark comedy, but not consistently funny. Some gags land sharply; others drift by without impact. There are elements here that feel like the bones of a very good “dad movie”—crime, moral ambiguity, dry humor—that could thrive on streaming or VOD where expectations are recalibrated. The original title, Huntington, was arguably more apt and intriguing. How to Make a Killing sounds generic and pulpy in a way the film itself isn’t. We also have a wild ending. At one point, Powell’s character ominously states, “this is a tragedy”—foreshadowing the ending that can be interpreted both as inevitable downfall and darkly comic irony.

The score by Emile Mosseri is genuinely strong, elevating scenes that might otherwise feel flat. However, the color grading is distracting and never quite works, giving the film an artificial sheen that clashes with its grounded ambitions. The cinematography and editing are serviceable at best—competent but rarely dynamic.

Ultimately, How to Make a Killing doesn’t have enough bite to be a great dark comedy, but it’s far from a misfire. It’s an uneven yet engaging crime tale buoyed by Glen Powell’s star power. Once again, he proves he can command attention even among a stacked ensemble and shows clear potential to ascend to full A-list leading man status. Whether tragedy or twisted triumph, this is a solid, mildly satisfying watch.